Picture a Bar of barely 2,000 members in which your first step up the ladder depended more on whom you knew than on what you knew; you could pass your Bar finals with nutshell notes from the private tutors Gibson and Weldon with no obligation to attend the solitary Inns of Court law school - as long as you had also eaten 36 dinners at your Inn; the Inn had less than 10% women, and still fewer ethnic minorities, then segregated in their own chambers; you had to pay £100 to your pupil master for the privilege of learning from his trials and errors and then without further education, you were let loose to practice on your own.

Picture a Bar that was riddled with restrictive practices where you had to pay to appear in court on a Circuit other than your own; no QC could draft pleadings or appear without a junior, who had to be paid 2/3rds of his leader’s fee and clerks by convention took 10% of the Chambers income; Chambers were small, in London they were located almost completely within the confines of the Inns, bearing names which were their addresses and not borrowed randomly from legal giants of the past; the departure of a tenant to another set was considered on a par with a divorce; a male barrister not accoutred in appropriate clothing - wig, bands, white shirt, waistcoat (and for female barristers a dark jacket and skirt, as women wearing trousers was not permitted until 1995) could be met from the Bench with the curious formula “I cannot hear you” and had nothing to do with his or her audibility; and clerks often insisted that their young men bought bowlers to doff to a passing Judge in the street.

Picture a Bar in which the acquisition of Silk and elevation to the Judiciary depended entirely on the Lord Chancellor’s say so; the Bar had a monopoly on Judicial appointments and there was only one woman on the High Court bench; it was assumed that all barristers would (or should) aspire to the Bench, so those who were appointed and repented their choice and quit were treated as heretics.

Picture a Bar in which solicitors were regarded as inferior and not an equal part of the legal profession with whom fraternisation, let alone marketing, was a breach of the Bar’s code thus leaving the barrister’s clerk as the sole vehicle for his promotion; and conferences had to be held in the barristers’ chambers, not in solicitors’ or clients’ office.

Picture hearings, all in person, when Judges had no duty to prepare and no reading days were allocated; orality reigned supreme, written submissions were not only not required but actually rejected; Judges, without specific training for their new task, acted as referees rather than managers with no eye on the clock or fear of scrutiny by a Ministry of Justice official; cases could be adjourned for “Counsel’s convenience” or because the Judge had a “public duty to perform” (sometimes a euphemism for attendance at a royal garden party); the High Court was still trisected into Queen’s Bench Division, Chancery and that ungainly medley Probate, Divorce and Admiralty; quarter sessions and assizes had not yet mutated into the Crown Court; the Apex tribunal was still part of the legislature in the House of Lords; there was no access to Strasbourg or (if only later and then temporarily) to Luxembourg.

Picture a wholly analogue, pre-digital age in which all elements of the legal system, from the first stages in litigation to the research underpinning it, were an ineluctable part.

Now fast forward to the present era of miscellaneous acronyms - EDI, BSB, CPD, CMC, ADR, CPDR and so on, and tell me that in 1967 the Bar did not dwell in another country.

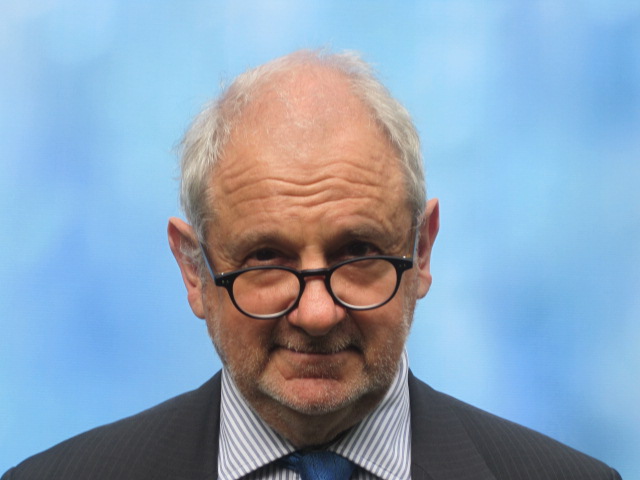

If you don’t believe me, you can cross check my memoir MJBQC: A Life Within and Without the Law. With the published memoirs of, or interviews with, my august contemporaries John Dyson, Simon Brown, Anthony Lester, Mike Mansfield, Helena Kennedy, Graham Boal, Ivan Lawrence and Wendy Joseph, and that done, I challenge you not to acquit me of exaggeration or fantasy.

Throughout my career the Bar has been said to be threatened with extinction as an independent branch of the legal profession. But reports of its demise, like of Mark Twain’s death, have been greatly exaggerated.

The Prince of Lampedusa in the novel The Leopard said: “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change”. The Bar, with the critical exception of its fidelity to its core ethical underpinnings - the cab rank rule and the paramount duty to the Court - has changed in more than half a century almost beyond recognition. Still as Tom Bingham memorably reminded us “It’s where the magic is”.