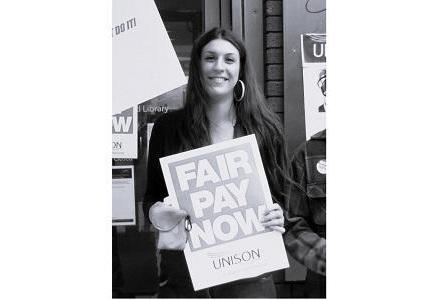

For International Women's Day 2022, Lucy Chapman says the support and solidarity experienced between women in the trade union movement is also alive and well at the Bar.

Amidst the airbrushed images and vacuous hashtags it can be easy to forget the significance of International Women’s Day (IWD). IWD did not begin as an opportunity for celebrities to promote their latest brand on Instagram (does anyone else cringe when they read #girlboss?), nor was its aim to platform super-rich CEOs who were handed their family company on a silver platter.

Originally IWD was a show of solidarity between women all over the world, with an emphasis firmly on sex discrimination and worker’s rights. That solidarity remains as much needed today as it was then; women are in many areas still considered second class citizens.

Globally, the abuse of women such as trafficking, femicide, domestic violence, denial of reproductive rights, sexual assault and FGM continues, as does the fight for equal recognition in society and law. Women in the West are not exempt from these issues. Iceland is the only government in the world with equal number of women to men in its Parliament, whilst the number of women MPs in Britain sits at just 35%, the highest percentage in history, but still far out of line with the population ratio. We remain an afterthought in key areas like health and medicine, where research is vastly performed in favour of men, with conditions specifically affecting women remaining undiagnosed for longer and often misdiagnosed.

Although part of the modern IWD is to celebrate female achievement, there is a sombreness that is equally important. IWD for me ought to celebrate those who fought, and often sacrificed, to further women's and workers’ rights in the past. It is a time to reflect on the current barriers to women globally, recognising our own battles in the UK and sending the spirit of solidarity to those internationally who may be facing worse. Sadly, it seems that spirit is often lost.

Before coming to the Bar, I spent several years as a trade union representative, advocating for workers from all walks of life at workplace hearings and assisting with disputes. I had strong women role models in the union who saw potential in me and took me under their wing, which enabled me to progress and become more involved, eventually becoming Branch Chair. That solidarity and support was key to progressing in a traditionally a male-dominated field.

I was lucky enough to have an employment law diploma paid for by the union that I studied for a year in the evenings, after I finished work in an inner London public library. This gave me an education in worker’s rights and the historic trade union movement. The disputes that affected me most were the Ford Dagenham strike and the Grunwick strike.

I want to highlight a couple of the many achievements of women workers in Britain, in the hope of inspiring with their courage and strength. You may be familiar with the Dagenham strikers from the excellent film "Made in Dagenham". At the time in 1968, women were paid less than men, the general attitude being that men were the breadwinners, women ought to be at home raising the children, and if women did work it was merely for 'pin money'. More than that, the media portrayed women as not deserving of an equal wage as their work was less worthy, warning that if the floodgates were opened, women would be taking away men’s jobs and wages. The catalyst was when textile workers at Ford Dagenham – all female – were reclassified as a lower band of unskilled labour and received a pay cut, whilst men were not. The women challenged this, and to make their point, withdrew their labour, resulting in a total standstill in production. Following the strike, the Ford workers were still paid less than their male counterparts, only less so, for years to come. The strike inspired the National Joint Action Campaign Committee for Women's Equal Rights, eventually resulting in the Equal Pay Act 1970. Despite this, the act did not come into force for another five years, and pay has remained unequal for far longer.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with it, Grunwick was a textiles factory operating in the seventies which employed South Asian female workers for a pittance. Many of these women had fled Uganda, where Idi Amin was persecuting Asians, and settled in the UK as British citizens of the empire. In 1976, Britain was not a welcoming host to its colonial ‘children’. The workers were qualified for a range of professions, but at the time the door was firmly closed to them as immigrant female workers. Conditions were poor, as they were for many female factory workers at the time, and racial abuse and degradation from the employer was rife. The Grunwick women did not take this laying down, and decided to join a trade union, embarking on collective action that has gone down in history. The Grunwick strikers obtained unprecedented support for what was a women’s strike, and beyond that, an immigrant workers strike, from trade unionists all over the country. Heavy weight, male-dominated unions responded to their call to arms, and in a show of solidarity, trade unionists came to London to support the Grunwick strikers. All kinds of workers united in support of the cause.

The Grunwick strike ultimately failed. These women were in essence sold down the river by the TUC, which at the time was predominantly a male, white organisation, who withdrew support for the strike, capitulating to pressure. The Grunwick women went on hunger strike in protest, which was unsuccessful. After two years the strike ended, but it was not for nothing – equal pay for women was an issue that refused to go away, and the country knew we meant business.

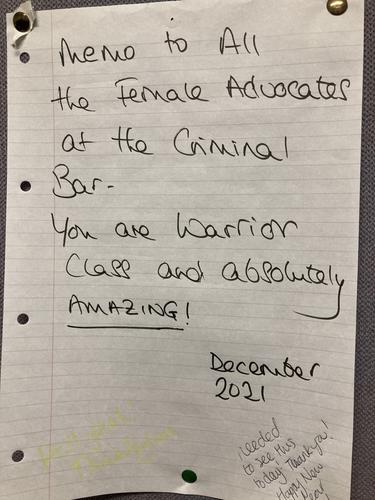

We can learn from the Grunwick and Ford workers, and the strength of organising collectively. Now, the criminal Bar is considering collective action in order to drag conditions into the 21st century. Overall, women at the Bar remain poorer paid, and discrimination can seem at times to be somewhat custom and practice. Despite this, the solidarity and support I experienced between women in the trade union movement is alive and well at the Bar. There is a fine tradition of taking the time to give advice and support to each other. Things need to change, and that change may be gradual, but I have faith that women barristers will continue to fight for our rights.

Before she walked out, the leader of the Grunwick strikers, Jayaben Desai, said: "What you run here is not a factory, it is a zoo. There are monkeys here who dance to your tune, but there are also lions here who can bite your head off. And we are the lions, Mr Manager! I want my freedom!"

Remember those that came before us. Recognise their struggle and that of women all over the world today. Be the lions.

Lucy Chapman is a barrister at 1MCB Chambers.

Access more information and blogs about Women in Law